Why are we so weird? with Michaeleen Doucleff

"That thinking is such a mismatch with our evolution and history."

This Q&A is part of a series of conversations with people who are forging meaningful lives in a time of chaos and unpredictability. These interviews take time and skill to produce, but I keep them available to all subscribers rather than paywalling them. If you value the themes explored in these conversations, consider upgrading to a paid subscription.

Every so often you come across an elegant and simple idea that helps you reframe a lot of how you think about the world. A couple years ago, when I was pregnant, I came across one such idea in a parenting book.

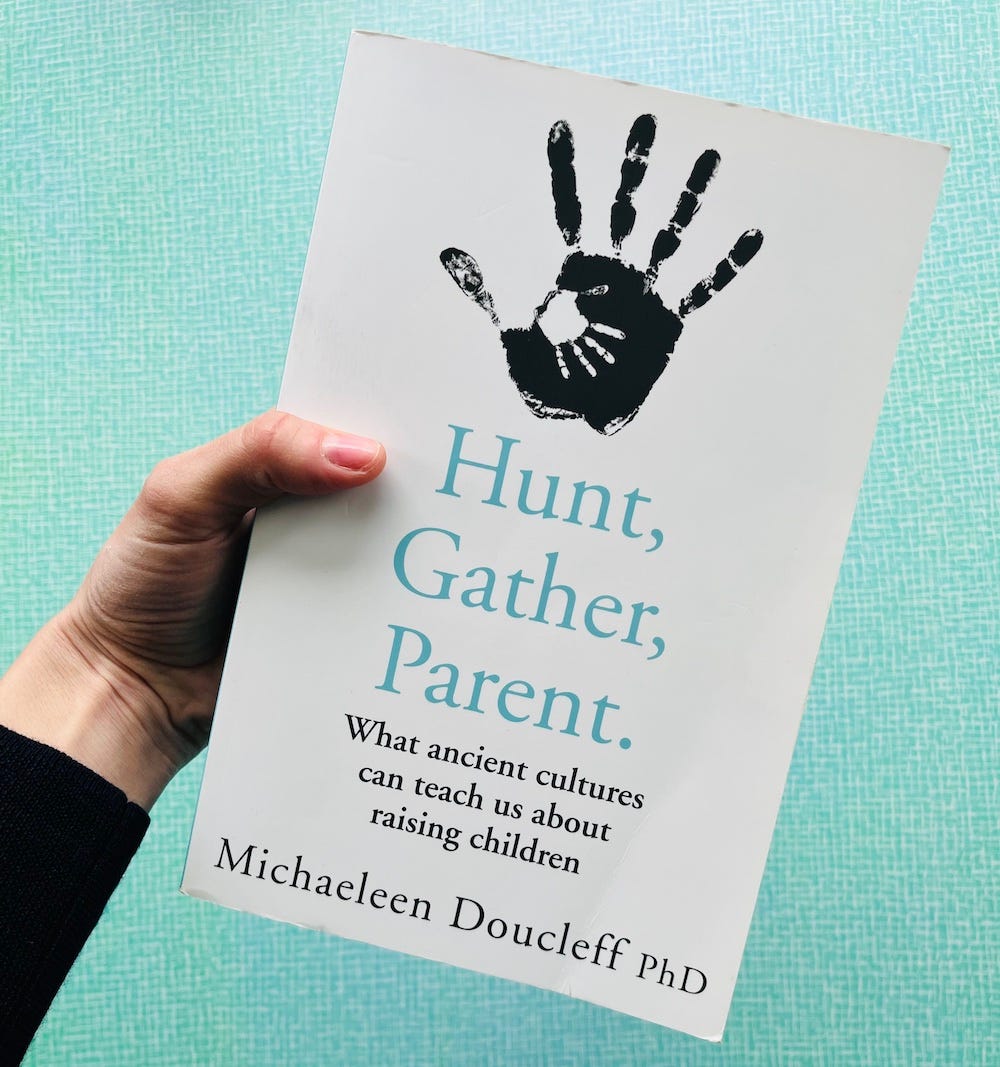

The idea is actually an acronym: W.E.I.R.D. We don’t just live in a western society, we live in a Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic one. On the face of it, all those words sound like positive descriptors, right? But the argument of the book Hunt, Gather, Parent: What ancient cultures can teach us about raising children, by Michaeleen Doucleff PhD, is that parenting in a WEIRD context makes life and caregiving much harder than it appears to be in other, supposedly less “advanced” cultures or societal structures.

Doucleff uses her background as a rigorous NPR science correspondent — coupled with her very relatable frustration at parenting a then-toddler in San Francisco — to figure out what communities like the Mayans in Mexico, the Inuit people in the Arctic, and the Hadzabe people in Tanzania are doing that we’re not. She manages to do all this gracefully, without relying on any of the icky, exoticizing tropes that you might expect from a fancy white reporter lady who is spending time with so-called traditional cultures. She also takes her toddler along for the reporting journey in the book, which is a kind of bravery few can claim to possess.

Whether you’re a parent or not, Doucleff’s book is interesting because there is a lot that WEIRD parenting styles can tell us about WEIRD societies as a whole. That’s why I wanted to interview her, and do so in the most expansive way possible. Even if you never want to have kids, if you were raised in a WEIRD society, it’s worth investigating the norms you may have inherited from that.

In addition to talking about the very WEIRD divide between parents and non-parents, we talked about the limits of what science can tell us, the overcorrection of therapy culture and so-called cycle breaking, her fear of challenging the cult of American individualism, and why the phrase “it takes a village” may be misleading.

This conversation made me feel hopeful. I hope it does the same for you.

Rosie: I wanted to start with the WEIRD framing, which I know is not originally your idea. However, I first came across it in your book and I’ve found it so helpful ever since. Because what are we saying when we rely on the descriptor “western?” It’s too general — WEIRD puts a more precise point on it.

I wonder if there was a moment in your reporting or writing when you realized that what you were grappling with wasn’t just modern or western parenting, but specifically, WEIRD parenting.

Michaeleen: It really dawned on me in that moment I write about in the book, when I was sitting in the airport in Cancun after spending a week reporting a story about children’s attention spans on the Yucatán Peninsula. There was such a stark contrast between the way the Mayan parents and children interacted and the way parents and children were interacting at the airport. My mind was just blown. It really was like, oh everything that I thought was good, optimal, right, progressive, modern — all these wonderful words — was just this mirage.

R: Since I read your book I’ve noticed a much more prominent conversation about some of the limitations of being WEIRD. The nuclear family, individualism, this atomized way that we live — both for parents and non parents — is actually the aberration or outlier. And it makes life really tough for a lot of folks. Have you noticed this conversation getting louder?

M: Yeah absolutely. Individualism is this thing that is so deeply rooted in our culture and I was afraid to talk about it even. When I first started reporting on this, I was afraid to say that a big part of the problem here is the individualism embedded into WEIRD societies.

R: Because there is a tension in this argument, right? Part of that individualism is this widely-held belief that it’s really positive to overcome your past, to be a “cycle breaker” as a parent. A lot of the wildly popular parenting advice these days — espoused by people like Dr Becky Kennedy and Janet Lansbury — is explicitly about learning how to parent how you were not parented. This is what a lot of millennial parents I know are focusing on.

But then you have a kid. And you realize the fatal flaw in this idea of being the master of your own destiny, of prizing independence and having strong boundaries: You weren’t supposed to do this alone. You were supposed to have help, from family and otherwise.

It feels like there’s an overcorrection there, and I see it in a lot of people I know. The culture views going to therapy and overcoming negative generational patterns as really positive, but by doing that we’re also potentially blocking ourselves from receiving the help we need and deserve.

M: Yes absolutely. You’re exactly right. I remember through most of my childhood and teens, I was thinking: I have to teach myself to be alone, I need to be independent, I need to be okay with being alone.

Number one, that’s not how we were made. If you want to go beyond parenting, that thinking is such a mismatch with our evolution and history. We are these incredible social creatures. And so whoever put these ideas into my mind is just wrong.

And what I decided in my 40s is that it’s all bullshit and I don’t need to be alone, I don’t need to teach my child to be alone or independent. What I need to do and learn — and am still learning — is how to cooperate with people, and connect. It’s such an irony: the more I connect and bond with my daughter Rosy, the more this child becomes independent.

That’s the problem: You need to learn boundaries in a culture of individualism but at the same time, when you actually learn to connect with a person in a cooperative manner — what you find outside of western culture — there is no boundary. It’s a mutual respect, and reciprocal respect, and so you can let the boundary down.

R: Right, like boundaries are necessary in an individualist culture where a lot of people are unwell, but it’s not really how we’re meant to interact with each other.

M: This is where this whole parenting book and research started for me. Two [social scientists] Barbara Rogoff and Suzanne Gaskins — who are contemporaries and work together — both talked about it: In western society, parenting is this relationship of who is controlling who. And once you treat a child in a way where you think they’re controlling you and you’re controlling them, you’re stuck in this awful tension.

R: Maybe part of the solution — which you explore in your book — is this idea of alloparents, or non-parental caregivers that share the load as part of daily life. I spend a lot of time reading parenting Reddit threads and the refrain is always: “I have no village.” People often debate about whether it’s possible to create your own village, or whether modern parents are just screwed.

I loved the line in your book about how you feel at 4pm on a Sunday afternoon when you’ve been doing the work of what should be four adults all weekend parenting and entertaining your daughter. I so relate to that feeling. I wonder since you wrote this book if that’s changed? Have you found that in your life? Do you have a village now?

M: Absolutely. If you look around at some non-WEIRD cultures, including hunter-gatherer ones, the alloparents are often not related to the child. And in many cultures — pastoralists, fishing cultures — families are split apart or geographically separated, either by choice or not. And yet, in these societies you see this enormous amount of alloparenting. So this is not just a family thing that has to happen. Alloparents don’t have to be related to the child.

I recently wrote a piece and the researcher said to me, “there’s this expectation that parents are able to do it by themselves.” This is the problem, she said, the expectation itself — before you even get to the structural policies that are basically saying do it by yourself. And most people, when you look closely, actually aren’t doing it alone, because it’s impossible. [They have paid help, government assistance, informal help etc.]

The story in hunter-gather communities and many other communities is that you need tons of help. Everyone needs tons of help! And so everyone gives everyone else tons of help! We need a new story.

So in my own life. We actually moved to a tiny town in Texas near the Mexican border because I wanted a place where people value alloparenting. And so we have tons of help. Right now there’s a mom with her three kids helping, and we’re going to have a party shortly with some other families coming.

R: So how did you choose that town? How did you know it would be that way?!

M: Laughs, well it has an enormous amount of influence from rural Mexico, so that helps. But I came here and I could just kind of see it. My focus is not quantity of alloparents. Its quality. And if you look around the world you’ll see this too. Two very good functioning reciprocal alloparents can do 90% of it.

R: This brings up this divide between people who have kids and people who don’t. And the fact that divide even exists is because we don’t view caretaking as a group effort in WEIRD societies.

Parents feel isolated in how hard it is because up until the moment they’re handed that baby, they actually have no fucking idea what is involved in keeping this thing alive. They’ve never helped anyone else do it or been around it regularly. And those who are childfree (by choice or not), as well as single people, feel isolated because of the emphasis on the nuclear family. They may feel that they don’t have any stake in how kids get raised.

I used to think that way before I had a kid, but now I think it’s insane. When you think about the growing number of people who are not having kids because of the climate emergency — those people, by virtue of caring about the future of our planet, should care about children that inhabit it.

M: Right, that should be an argument for caring about other people’s children more. Again we bump up into individualism and I would also argue you bump up into a lot of what parents feel is the right way to raise a child. There’s a lot of shame in asking for help. In getting help. There’s an issue in trusting other people. When you're trying to optimize parenting — which I think is a lot of what parents try to do, optimize the child — why would you trust somebody else to do that? There are all these things stopping us from admitting that we can’t do it alone. But as I said, the biggest problem is the myth is that we can do it alone.

R: The only advice I would dare to give someone who is expecting or someone considering kids at this point is don’t delude yourself that you can do it alone. Accept the help, set up the infrastructure for help, really try to internalize how abnormal it is to try and do it all alone. That mindset shift has helped me a lot.

M: Yes, and if you really want to “optimize” the child, then the child is made to have these people in their life. People often say, “my kid loves being around other people that aren’t me.” And I’m like, “Yes! Because you have a homo sapien. They’re wired for that.” So if you find it hard to accept help for yourself, do it for your kid. They will benefit.

R: I know a lot of people for whom moving to be closer to family is not an option. They either don’t have family, or that family isn’t willing or able to help, or they can't move for whatever reason. So what advice would you give to a person who wanted to build or create find alloparents and to be that for other people.

M: Number one, start small. You’ve got to just find one or two. It’s not a village. This is a misnomer. It can be one or two people. And then it’s just keeping your eyes and ears open.

There are parents in the same exact boat everywhere. Find that person: “Hey does your kid want to come over?” Our house is always open for kids to be dropped off. I’m welcoming people into our home because I know that this is important. And then you can start to find one or two people who want to do this together. You’ve got to open your home and your life to them.

So neighbors are a great place to start. When we first moved here I made an effort to connect with all the neighbors, baking them something, really putting forth an effort to connect and value them. This summer, a nine year old moved in next door, so I went over and introduced myself and then she came over and now the kid comes over all the time, she eats dinner with us. She’s two years older than Rosy and she’s a great alloparent. Kids can be the best at this.

R: I like the advice to open your home first. Create the conditions of what you want to the extent that you can.

M: She’s a little older now, but when Rosy was little, If I had an extra kid here, it was so much easier than her being by herself. I want them here. I value the extra child here.

I’m telling you there are other parents that want the same thing. It’s all about the buy-in from other parents. Is the mom afraid of everything I feed the kid? Okay then it might not work. But if the mom is dropping the kid off on Saturday with little notice I’m like, “alright, I got ya.” It becomes informal. We’re helping each other, it’s casual. This is not scheduling things four weeks in advance.

R: I love that answer, it makes me feel hopeful. And I think some of that applies for single/child-free people too, who feel lonely or disconnected.

M: Oh, there’s so much hope. We’re starting with so little, so even just a small improvement feels enormous.

R: You’re a science correspondent and you have a PhD. But a lot of what I loved about your book is that it was not evidence-backed in a lot of places. It was a lot of common sense, close observation, and instinct meeting tradition. You even say in the book that parenting is notoriously difficult for science or peer-reviewed literature to provide answers for — going to outer space is easier to figure out. I wonder if that lack of provability was hard for you to accept in writing the book?

M: It's still something I'm learning. I think that science has limited our collective mental health in some ways. Because I think there are so many things you can't prove with randomized controlled trials. And yet, you can live them day after day. And I think the Covid pandemic even reinforced this in me.

Like wow, there were all these things that we thought about infectious diseases, airborne diseases that were just completely wrong. And I started digging even more, there are so many things in psychology that we think are the absolute truth of our minds, and you go back and you look at the data and the data are awful. Every month there’s a new thing where I’m like, “wait a second what’s the data on that?” And I go back to the data, which is from the 1960s, and it just falls apart.

R: It’s so interesting and weirdly validating to hear you, a science correspondent, say that. I also think we don’t think about the power structures that determine the things that even get randomized control trials. There are so many things built into our lived experience that will never get studied because of all sorts of institutional biases or profit motives.

There are also plenty of things that we don’t even need evidence for. The endless debate around cry-it-out sleep training is a good example. I don’t need peer reviewed evidence to tell me what to do there, because the physiological and emotional reaction my body had to my helpless infant wailing was enough to tell me that was definitely not a good idea.

M: That’s a good example of where it’s hurting our mental health. And where on earth did we come up with this idea that we need a randomized control trial to tell us what to do in our lives? It’s a mirage. It’s this fantasy thinking that science is going to tell us what’s right all the time.

R: I think science can tell us what’s right sometimes. It’s certainly a useful tool. But we have all these other faculties that we’re not using because we’re over relying on that one: emotion, instinct, embodiment, awe. I think in parenting you really feel that.

M: I didn’t want to treat Rosy the way I was treated. I felt this so strong in my heart, and in this eerie part of me that I was like, “Okay maybe this thing I built my life on — which is science — maybe I need to start questioning it a little.” Something that was run by white men the entire time, remember that too.

R: The part of your book I loved from a practical point of view was when you said I don’t have to take my kid to child-centric activities all the time, nor do I have to stop what I’m doing to engage in enriching play all day. I remember the example of the little Mayan girl helping make the tortillas on the hearth in the center of the home. She had learned how to do it in these tiny, age appropriate steps from very young. I feel like letting a toddler use a stove or oven would be considered child endangerment in a WEIRD context.

This idea that family chores are an ideal play format for young kids — I have to say, it’s really borne out so far. The other day I was cooking and my 18 month old son spent 30 minutes playing with vegetable scraps on the floor, totally engrossed. This is the kind of silly stuff I encourage and involve him in: Putting one piece of cat food in the bowl at a time to “feed the cat.” Handing me one fork after another from the dishwasher. He loves it.

M: It’s not silly. A lot of the cross-cultural researchers say that a child being in the adult’s world and doing things with you is way more enriching to the child than the kinds of activities we tend to think of as enriching. Suzanne Gaskins, who I mentioned before, used the term deprivation: These highly child-centric environments are a kind of deprivation, they are not preparing the child for what they need. Because learning to be with older people, learning to be quiet, learning to be calm, learning to play alone — these are their own forms of stimulation and enrichment. What our society thinks of as an enriching environment for a child is in many ways a deprived one.

R: Right, and I think there are two ways to look at this: One is that this approach just makes parenting easier. They learn to help with chores over time, and I don't have to go to sing-song baby classes or soft play every Saturday. Win win. But I also think that there’s this deeper element.

This WEIRD model of parenting where parents are devoting all of our resources to enriching their lives — it doesn’t really prepare them for how life is going to go, does it? Life is not going to be this unbroken journey of excitement and wonder if parents just optimize and work hard enough to make it so for their kids. There will be a lot of boredom and hardship and angst and suffering. Especially with the future we’re looking at.

So I wonder now that Rosy is a bit older, what is the world that you are preparing her for? What values and skills do you think are going to be important for her to have?

M: Number one I am giving her what I never had, which is feeling connected and loved. I felt that my parents loved me, but I felt incredibly lonely in my house. I felt like there weren’t these people that had my back no matter what. And that’s what I want to give Rosy. Whatever goes wrong, I’m here, we’re gonna work it out, we’re going to figure it out. To really have that, you can’t have individualism mindset.

The second thing is I really want to teach her that giving and helping other people is this incredible source of joy. And I think our society is just starting to understand this. It’s not just about transaction, what am I getting from you — it is a source of joy. I want her to grow up and find something that she does and lets her access that source of joy. That’s it.

R: That’s beautiful.

M: I’m not trying to optimize her. If she goes to the tiny university in our small town, and pursues a profession where she feels this cooperation, this sense of giving, I would be more than thrilled.

You can find Michaeleen Doucleff’s work for NPR here. Her website is here.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoy this newsletter, it helps a surprising amount if you forward it to a friend or two, or leave a like or comment below. If you’d like to support me further, you can upgrade to become paying subscriber here. Thanks to all of you who already do that. It means a lot.

I feel like a broken record sometimes telling everyone I know how dysfunctional our society is on so many levels. Like, we've designed a culture and society that is the worst possible environment for us as a deeply social species, including our children. I have to check out this book now!

As someone without kids, I’ve kind of given up on investing in friendships with parents. I’ve found they’re too busy with child centered activities to make the investment worth it for me. I reach out to them but they have a kids sports event (that they don’t invite me to). Or I’ll ask if I can come over, bring them dinner, and we can just hang out, but they hd a long day at work. I’d love to be included in their community and can offer a lot of support but they tend to exclude me in favor of just being a little nuclear family. I so appreciated how this interview addresses the child-free. We can be allies. I’m happy to help (and I have the time since I’m child free).