Should we lower our boundaries? with Alice Wilkinson

“Being around and investing in other humans is uncomfortable.”

It’s been a while since I’ve published a Q&A in this newsletter, so I’m excited to kick off a new series of interviews exploring how to build a village from a range of viewpoints and angles. If you’re new here, you can view past Q&As from the newsletter here.

There’s this tension in modern life that I think about a lot. We’re all lonely and say we want more connection. And yet, at the same time, we’re all products of an individualistic and increasingly well-therapied generation who say things like, “that doesn’t work for me” and “I’m putting up a boundary” when our interactions with other people get hard.

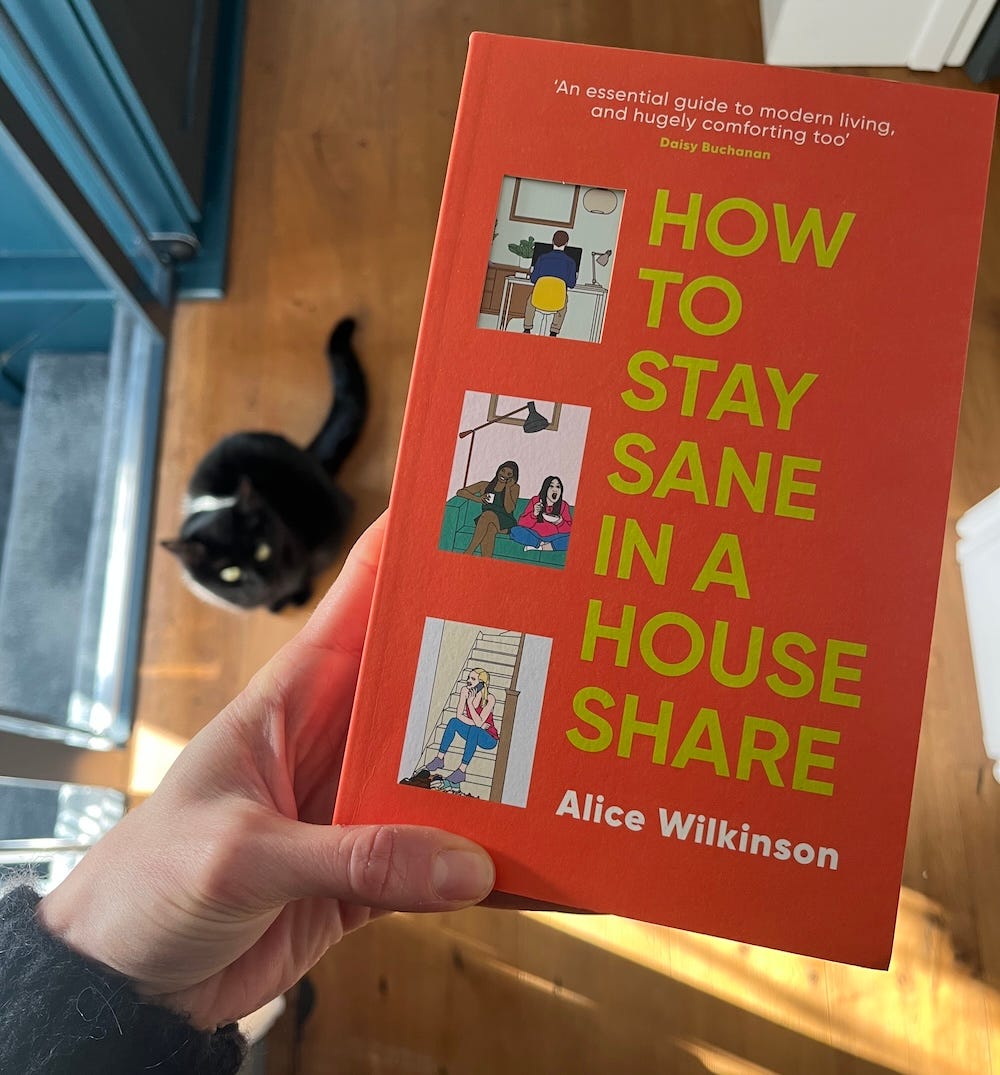

Indeed when we talk about boundaries, it’s almost universally seen as a positive thing in our culture. When I was reading my friend

’s forthcoming book — How To Stay Sane in a House Share, out March 6 — I started to wonder if perhaps our obsession with boundaries is actually part of the problem.For a lot of reasons, people are living in house shares for much longer periods of their adult lives than ever before. Alice’s book is not about the political and social factors underlining that shift. It is about something else, which I’d argue is more useful: the personal and interpersonal work we need to do in order to make these living arrangements not only bearable, but also more nourishing and long-lasting.

Though I certainly had a long stint of them, I no longer live in a house share. However I still found Alice’s book fascinating. It reads almost like a personal development book, providing the reader with skills and techniques — from understanding our attachment styles and interrogating our knee-jerk response to conflict — that are useful to literally anyone who wants to live harmoniously alongside other humans.

Remember, when we talk about building a village, we’re not talking about building a utopia. Figuring out how to navigate the complexity and mess of human beings is a huge part of the work. Actually, it’s the work. And as I’ve written about before in this newsletter, the way that we live now takes us away from that work, deluding us into believing it’s easier if we do everything alone.

Alice’s book — and our conversation below — reminded me of what can happen when you lean into the complexity, embrace the friction of other humans, and let it change you.

I was struck reading your book by the fact that no one had written it yet — a sign of a good book! What was the moment you realized the house share experience needed a deeper look?

I think it was my 3rd or 4th house share. I wondered: Is it me? Or is this just house sharing? Is there just a level of investment that I’m not prepared to make in these people and in these places? Or are we just not being told how to do it?

A lot of the skills you end up exploring in the book are still ones that would be helpful in a traditional romantic relationship. It’s not like you move from a house share into a family home and stop being annoyed by the dishes in the sink. That introspection — the inner work you describe how to do in the book — is applicable to almost every relational structure that we have.

The penny that dropped for me was that it’s an investment. And that’s what I wasn’t doing. And that’s what a lot of people don’t do because we view house sharing as a temporary time period, it’s a time of life that we expect to leave. Which means that people don’t invest in that space. There is an investment in romantic relationships and in a family structure that people feel they don't have to do in house shares. And that’s where we get stuck.

We don't really ever speak glowingly ever about house shares. It’s always about terrible roommates having sex at strange times and people eating your food. But your book reminds the reader what they can actually offer: support, companionship, camaraderie, rituals, intimacy. All these things that we say we want! So I wonder, did you come away with a fondness for house shares?

When I sold this book, I thought I was going to be writing it retrospectively. I was going to write to my younger self about what I wish I’d known. And then my relationship broke down and I was terrified because I had all these bad memories of house shares and suddenly I had to move back into one while writing a book about it.

Then I started interviewing women about them and I was taken aback because I was expecting to sit in interviews hearing how people were desperate to get out of them. But actually that is not what I found. Yeah there were problems, but there were so many stories of connection. And I visited some of the house shares and I could feel that and see that. And it actually made me excited about going back in.

A lot of the things we’ve been told define success in adulthood are becoming less available to us: home ownership is a big one. And the very idea that we should live in our own individual houses with two to four people is a very modern, individualist western idea. Whereas the house share almost fits into this more collectivist setup — this infrastructure of support that’s built into our lives. It is certainly not glamorous, but it’s the kind of thing some people are realizing we need more of given the state of the world.

When I was researching, I did find it amazing how the political structures and Margaret Thatcher's era created this individualism. Changing people’s mindset from being community-minded to very individualistic. When I was mapping through the history of house sharing, you can just sort of see how that’s created this ideal vision for older millennials like me who grew up with parents who just … got a house. That was just the expectation.

For me, even now, it can feel slightly shameful to be house sharing. But the women that I interviewed who are ten years younger than me, they don't want to move out of them. They are like, “this is the chapter for me to live with friends, this is the chapter for me to live as a community.” They are celebrating them in a way that I wish I did. I don't know if it’s because they are further away from our parents' generation, or they just see that these structures are imposed on us.

There’s a version of this called intentional communities where people our age, and a lot of people with children, are actually seeking this “alternative” living arrangement out. And the only difference perhaps is that unlike the transient nature of a London house share, you're choosing it and you’re putting a little more effort into the structure and rules. There seems to be a growing recognition that the default setting maybe wasn’t that good of an idea in the first place.

Yes, that period has actually been quite short lived.

When I was in my relationship and still living with my partner, I had this experience where I finally has a space that I was entirely in control of: I’d painted every wall, every knickknack was on display just so. And yet I didn't feel fulfilled. I do remember feeling, “This is isolating. I don't feel that connected.”

When I realized that dream amounted to basically nothing, I was able to reenter house sharing knowing that ideal scenario had left me feeling quite empty. Whereas before I had this yearning for something I felt would fix everything. That’s what I want to tell people: that it’s something to cherish while you’re there.

What you’re arguing in the book is that with some intentionality, courage, and self knowledge, you can actually turn these transient house shares into something much more human and nourishing. That in some ways, they are more similar to how we’re built to live.

Yeah and I would say that attitude is contagious. I’ve definitely lived in house shares where it felt like we’re all atomized and you’d take your toilet roll to the room and nothing was shared. And those structures make you feel isolated and strained and not connected in all areas of your life.

The thing that came up quite a lot is dissociation. When people are living in spaces that aren’t right, when you’re coming home and can’t share anything, it’s super lonely and you dissociate. But if there is one person that sets that precedent in a house share then everyone follows suit, it can change. But you kind of just need one person to say: Okay I’m going to take this on, I’m going to make it my thing to bring people together, and then it suddenly warms up.

It takes some courage to be that person. To say: I want connection, I can’t do everything on my own. It’s vulnerable to do that. Which is why so many of us avoid it whether in house shares or our wider social lives.

That comes down to this knowledge gap I think. No one had ever explained to me “when you get into a house share it’s a good idea to invest in people or chat to people in this way.” You don't hear that advice, because we all expect to move out of them. No one tells us how to build a feeling of home with the people we live with.

The concept of “boundaries” is something that, in a more collective, kinship based culture, doesn’t really exist. It’s a very modern convention, and a move away from the webs of obligation that have defined human existence for millennia. I started to wonder when reading your book if what we need is less boundaries, and in their place, more courage, self knowledge, and tools (which your book gives) to help navigate conflict. In other words, you won't need the hard boundary if you’re able to navigate conflict with the person who is pissing you off. The alternative is that everyone just retreats into their little fiefdoms because “this just isn’t serving me.”

Yeah, it’s such a good point. Being around and investing in other humans is uncomfortable. There are always going be uncomfortable things in any relationship and I think we’ve got so used to not feeling those. To avoiding those. I obviously moved from house share to house share when things got hard, and that’s why. I wasn’t prepared and I didn't have the skills to deal with the conflict

One of the quotes from a psychologist I interviewed really sticks in my mind: being a bad communicator isn’t a personality, it's just a skill that not many of us have. But it’s a skill that we can hone. And also over time I realized that being able to face up to the conflict and letting people know when they’d crossed my boundaries, was a kindness to me and to them. It was a way of me saying: you mean enough to me — and this place means enough to me — that I want you to know this so we can fix it.

How has reporting and writing this book changed your relationships at large?

Navigating conflict — I practiced that a lot when I first moved into my current house share. It was a real life-imitating-art moment. I had these times where I thought “right, if I’m annoyed about this I need to just say it because I’m writing a bloody book about it.”

And so I did put those things into practice and they were always, always so much less dramatic than I imagined they would be in my head. Even when I started working again in an office, I have found I'm much more comfortable being quite honest about things that are negative or have made me feel a certain way. Before, I would have just stifled them. I’ve got this reminder that it’s an investment and if I’m going to stay in this situation and I want to build on this relationship with whoever it is, I have to reveal that side of myself as well. And not just the nice bits.

I’m going to finish with a quote from the conclusion of your book, which I found so beautiful and applicable to literally all of us, house sharers or not.

“When we understand how to negotiate the twists and turns in a house share, something bigger shifts … It gives rise to a hope and confidence that extends beyond the four walls of your house. You see how powerful it can be to tune into what it takes to live harmoniously alongside other humans who, although they may not have the same dreams, vulnerabilities, and hygiene levels as us, nonetheless offer us connection, support, and — for a time — a feeling that we are home.”

You can pre-order Alice’s book here, and follow her on Substack and Instagram.

Thank you for reading. These interviews take time and skill to produce, but I keep them available to all subscribers rather than paywalling them. If you value the themes explored in these conversations, consider upgrading to a paid subscription. If you’re already a paying supporter, thank you — it all adds up.

Yes! I've lived this process as a young broke person in a shared flat where 4 of us actually *shared one large bedroom* (4 single beds in it, super cheap rent) and a small flat. And witnessed young adults in the family now going through the same journey, picking up people skills, building community, making friendships. I sometimes think that one of the unintended consequences of the current housing crisis (which is, for sure, a vile thing, from property speculation to grasping landlords) will be the building of rhizomic networks of solidarity and connection. The upcoming generation could be way less individualistic than past ones - and that will be a wholly good thing.

I love what you’re unpacking here. I do want to add that I think most people misunderstand what boundaries are. In my lexicon a boundary is another word for a choice I make from what I really want to do. I don’t understand why other people refer to putting up a boundary. I guess they must be saying that they don’t wanna do something? This is because I believe that boundaries have nothing to do with behavior, change requests and control.